Before the spread of steam mills, windmills were a characteristic part of the Great Plain's landscape. You can still admire a few remaining examples of this old milling technology today.

A hundred years ago, windmills were an integral part of the Great Plain's landscape. They are worth admiring not only for their once-essential function but also for their classic architectural beauty. More than a century ago, every farmer had their own grain milled, making these windmills an essential hub of community life.

From the late 19th century, the role of windmills, operated by skilled millers, was gradually taken over by the rapidly spreading steam mills, also known as "fire mills." This transition required the development of the Hungarian railway network, as coal, essential for steam mills, could not have been transported to the Great Plain otherwise.

Within a few decades, windmills were abandoned, most miller families went bankrupt, and they had to seek other means of livelihood. The only exceptions were areas where the railway did not reach. Near the farms of Hódmezővásárhely, 21 windmills were still operating in 1924. In fact, some of these sailing-rotor structures on the Great Plain were still grinding grain even in the 1950s.

Operating Principle

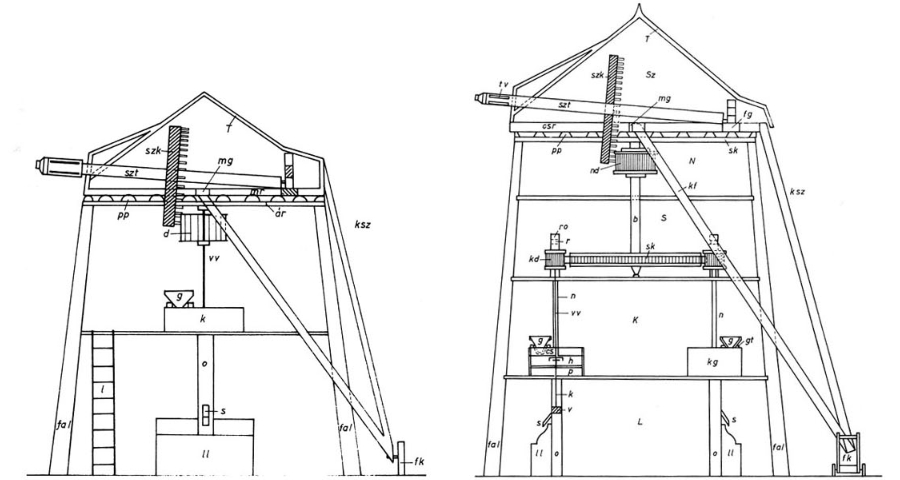

A defining characteristic of Dutch-type windmills is that the shaft equipped with sails, along with the integrated wind wheel— the gear that transfers the rotational torque generated by the sails to the mill’s main shaft—is mounted in a movable housing on a circular track at the top of the multi-story structure. One advantage of these windmills was that their rotation could be regulated in excessively strong winds; the position of the sails could be adjusted quickly and effectively, and if necessary, the machinery could be disengaged.

Thanks to these windmills, which have survived their time, we can still admire some of the most monumental creations of Hungarian folk architecture today. Some were built with wooden structures, using adobe and mud plastering. It was common for windmills to be constructed from adobe and later reinforced with a brick casing. In other places, they were built with brick or stone walls.

The structure of the simplest "papucsos" (slipper-type) or single-stone windmill and the top-drive windmill

Their interiors, ceiling structures, and roof frames are masterpieces of carpentry. The construction of their equipment required highly precise carving skills, but windmillers also had to be knowledgeable in working with wrought iron and steel components, as the rotating shafts, bearings, and joint mechanisms of the stone beds could not have been made without metal parts. The stone beds were designed so that the height of the millstones relative to each other could be adjusted as needed, depending on what was being milled and the desired quality of the flour. The wooden structures inside the windmill were crafted with exceptional care and aesthetic precision.

Keep your eyes open while exploring the Great Plain, visit these structures that take you back in time, and admire the windmills that still stand today.

Szegvár

The Szegvár windmill was built on an artificial hill on the eastern edge of the village around 1865. Its masonry is one meter thick at the ground level, gradually thinning as it rises. On the third level, it is 80 centimeters thick, and at the top level, only 45 centimeters. The wall consists of three layers: brick on the outside and inside, with adobe in the middle. The adobe between the two brick layers effectively absorbed the vibrations generated during operation.

The tower-type, top-drive windmill with two pairs of millstones was last owned by Pál Pusztai, who purchased the building for 3,000 pengő according to a sales contract dated October 18, 1937. In the spring of 1938, the Pusztai family began restoring certain parts of the still-operational but deteriorating windmill. A few years after the renovation, a strong storm broke two of the sails. From then on, the mill continued to operate with the remaining two. For a time, one pair of millstones was also powered by a motor, but fuel costs proved too high, so they returned to the original power source—the wind. Today, the windmill is a protected historical monument and welcomes visitors by prior appointment.

Karcag

In Karcag, one of the region's most valuable historical monuments is the Barna windmill, built in 1858 in a folk architectural style. The city once had sixty mills, including eleven windmills—today, only this one remains.

The windmill was built by Ferenc Gál on the outskirts of the city, on a hill-like elevation surrounded by a brick wall, to better harness the wind’s energy with its sails. The windmill was constructed with a rotating roof section and four sails. The four-story mill was made of brick. Work continued in the renovated and well-maintained windmill until 1949. After nationalization, a hammer mill was operated on the ground floor of the building. Its interior equipment has remained intact, as if the massive mill wheels and millstones had been grinding just yesterday. It is open on weekdays, but with prior appointment, both the windmill and the inn can be visited at other times as well.

Kiskunhalas

The windmill, originally built with a lower-drive grinding mechanism, was constructed by Antal Hunyadi in the 1880s using adobe bricks. In 1892, it was reinforced with a brick outer wall. József Sáfrik purchased it in 1901 and converted it into a top-drive system. The Sáfrik windmill took on its present form in 1934.

The windmill, declared a historical monument, was in operation until 1950. Over the past decades, its condition gradually deteriorated, and its sails rotted away. Recently, a complete restoration began, which was expected to be completed in the spring of 2020, allowing the Sáfrik windmill to become fully operational and capable of grinding once again.

Kiskundorozsma

Of Kiskundorozsma’s former 23 windmills, only one remains standing. The still-admired structure was built on a hill in 1821 to allow the wind to turn its sails more easily. Until 1920, it ground grain, and afterward, it was used for grinding fodder. In the rural countryside, people living in scattered farms often gathered at the windmill to exchange ideas and news. In fact, matchmaking and choosing brides frequently took place at the mill.

After the grinding workshop was closed, the building fell into a long period of decline until, on a rainy morning, it collapsed, marking the destruction of Dorozsma’s last windmill. The remains of the adobe structure were stored in a depot for many years until the city of Szeged finally renovated it in 1973.

In 2005, during the peak of the tourist season, the windmill was damaged again after a major storm. Since then, it has been renovated, and today we can admire it in its restored form as the only currently operational windmill on the Great Plain.